Health, housing, and history

For health, place matters

What determines whether or not you’re healthy? You may think about what you eat, whether you exercise, whether you smoke and your family medical history.

But you may not think about how your home affects your health - and you may not think about the factors that influence where you live.

For a home to be healthy, it should be free of:

- Cracks

- Holes

- Leaks

- Smoke

- Pests

- Old, peeling paint

In other words, a healthy home is a well-maintained home.

But some buildings aren’t healthy places to live.

Buildings with maintenance issues and disrepair can harm health. Across NYC, low-income neighborhoods have a higher percentage of buildings in disrepair – and Black and Latino people have less access to healthy housing.

Today’s inequality can be traced to a history of racism and neglect: a practice known as redlining resulted in segregation which, in turn, drove housing disrepair and led to these health disparities.

Let’s explore how.

Racism has determined where people live since colonial times.

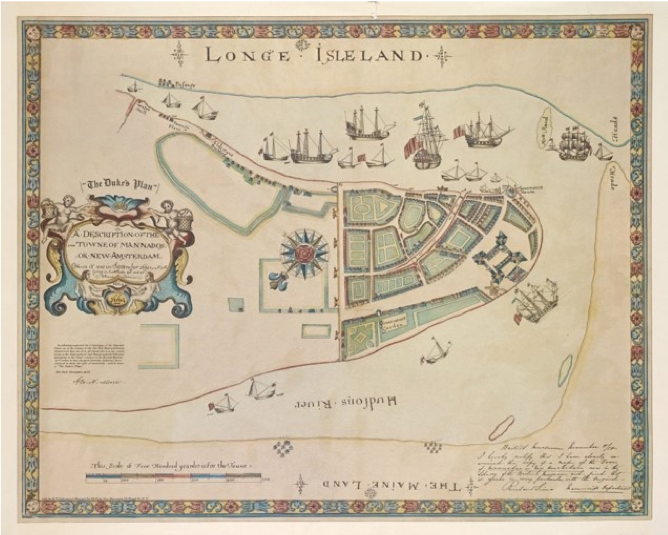

Racism has always played a role in residential patterns in New York City. When New York City was a Dutch colony, it was just the southern tip of Manhattan. Wall Street got its name from the city’s protective wall.

In 1661, when Black people petitioned the colony for land in the area, they were given land north of the wall, outside of the city proper.

Throughout history, many different practices have shaped racial and residential patterns in New York City. In the 20th century, a practice called redlining made racism a federal policy – with long-lasting repercussions for our housing and our health.

Federal policy drove residential segregation

In the 1930s, the federal government developed color-coded maps to guide loans to potential home buyers in cities across the U.S.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression caused a wave of foreclosures throughout the country. Unemployment rates were high and many people couldn't make mortgage payments. To help keep people in their homes, the federal government established the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC). Its goal was to refinance mortgages with better terms – less interest and a longer repayment times. This would help people make payments and avoid foreclosure.

However, to determine what loans they could safely guarantee, HOLC sent people to appraise neighborhoods in cities across the USA, and generated the discriminatory redlining maps that would guide the real estate industry for decades.

On these color-coded maps, neighborhoods were divided into 4 categories:

- Best

- Still desirable

- Definitely declining

- Hazardous

This classification was clearly rooted in racism, since neighborhood descriptions included statements like:

"Detrimental influences: Infiltration of Negroes. Mixed races."

The government denied loans to Black and Latino people trying to buy homes in redlined neighborhoods. Instead, these resources went to new White-only suburban communities.

The map below shows how New York City’s neighborhoods were categorized.

This was redlining

This process became known as “redlining:” systematically denying public and private resources based on where people live, targeting people of color.

Redlining helped drive urban segregation in the 20th century, as new neighborhoods were built for white people while people of color were forced into neighborhoods declared to be “declining.”

Since home ownership is an important way to accrue wealth, redlining drove economic inequality, too - by denying people of color the same opportunities for home ownership that white people had.

Other discriminatory practices maintain segregation.

Other real estate practices, like Blockbusting Contract selling Racially restrictive covenants, have maintained segregation.

Blockbusting was a practice used by real estate agents. Since many white people viewed people of color as a social and economic threat to their neighborhoods, agents would tell white homeowners that people of color were about to move into the neighborhood.

This would convince homeowners that their house's value would fall - and they would sell for a lower price. Real estate agents would then turn around and sell property to people of color for inflated prices.

Contract selling was a deceptive and exploitative real estate practice that targeted people of color with private loans to buy homes. These loans often had high interests rates and manipulative terms - in some cases, forcing the buyer to give up their home if they missed even one loan payment.

These contracts often made people responsible for paying back far more money than the house they bought was worth.

A racially-restrictive covenant is a clause in the deed for a property that prevents the owner from selling the property to people of color.

Racially-restrictive covenants were a way to enforce residential segregation, to ensure that people of color were kept out of white neighborhoods.

Today, housing advocates say that some landlords continue discriminatory practices, describing one landlord’s behavior this way:

“This landlord has a pattern of buying old, worn

out buildings in working class neighborhoods of color; letting the

apartments of long-term tenants fall into disrepair; and making them wait

months for low-quality repairs. Many tenants also say that this landlord

gives preferential treatment to new tenants.”

-from the Right to Counsel NYC

Coalition: Worst Evictor's List

These practices continue a legacy of housing racism, maintain residential segregation and, over time, result in disinvestment: when neighborhoods are deprived of resources that their residents need for health and opportunity.

Disinvestment led to housing disrepair

Throughout the 20th century, redlined neighborhoods deteriorated as they were deprived of private investment and government resources.

Landlords in these neighborhoods are less likely to adequately maintain homes. As a result, many homes have severe and chronic maintenance problems.

Explore NYC’s common housing problems in the map below.

Percent of households with healthy housing problems

Who shoulders the burden of housing disrepair?

These problems go far beyond inconvenience or mess. Disrepair can harm health.

Healthy housing problems - like maintenance deficiencies and general disrepair - are associated with many adverse health outcomes.

- General disrepair is associated with anxiety and depression.

- Some forms, like broken plaster and peeling paint, or cracks and holes in interior walls, can expose children to lead paint.

- Water leaks, broken windows, or toilet breakdowns can introduce mold - which triggers allergies, asthma, and can make chronic conditions worse.

- Pests, like cockroaches, mice, and rats can make asthma and allergies worse.

- The lack of an air conditioner places people at risk of death during hot weather.

As a result of the segregation and disinvestment caused by redlining, Black and Latino people have less access to healthy housing. They are more likely to live in buildings that have health-threatening maintenance issues.

These disparities persist across income levels

Black and Latino people have less access to healthy housing, but this isn’t due to higher poverty rates in these populations.

Black and Latino people with higher incomes are also more likely to live in buildings with serious maintenance issues - further suggesting that racism is behind these disparities.

These healthy housing problems can’t be fixed by a little bit of tidying up – they stem from chronic neglect of maintenance by building management and landlords, and old housing stock in disrepair after decades of disinvestment.

And the disparities in access to healthy housing are related to real estate practices that maintain segregation.

Racism and disinvestment show up in health data.

Disinvestment in neighborhoods of color leads to housing disrepair which, in turn, creates unhealthy homes. Disrepair, mold, and pests trigger asthma attacks, sending children with asthma to hospitals - an often frightening experience for both children and their caregivers.

As a result, the highest rates of asthma emergency department visits for children age 5 to 14 are in neighborhoods that are home largely to people of color.

A healthy home should be a right.

A home in good repair is vital. It’s protection from the weather. It’s a place for you to be safe. It’s a place where your family can grow and thrive.

But a poorly maintained, unhealthy home can’t provide a truly safe haven. Instead, it presents a dangerous environment.

So how can we create a city in which race - and racism - doesn’t determine whether you have an opportunity to stay healthy?

Policymakers and community advocates can support racial justice initiatives:

- Invest in neighborhoods harmed by a history of structural racism. Promote economic and educational equity and support Where We Live initiatives.

- Support Department of Housing Preservation and Development initiatives aimed at rehabilitating older housing.

Tenants and homeowners can tap into systems that are here to support you.

- Report maintenance problems to your building’s management. If your building manager doesn’t address issues, call 311 to file a landlord maintenance complaint.

- Get help if you need it: If you have been diagnosed with asthma and live in a home with mice or cockroaches, you may be eligible for a free home assessment by the Health Department’s Healthy Neighborhoods Program.

- Take action for fair housing with Where We Live.

Building owners and landlords should keep apartments safe and sanitary – it’s the law.

- Promptly fix problems that tenants report.

- Get rid of pests and mold, seal cracks, fix leaks, and improve garbage management.

- Hire a good pest management professional that uses integrated pest management (IPM). For information on how to safely manage pests, see the Health Department’s IPM toolkit.

Get the data

- Data on housing maintenance conditions come from the 2017 Housing and Vancancy Survey.

- Data on childhood asthma emergency department visits come from the New York State Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) Deidentified Hospital Discharge Data.

- Data on the race/ethnicity of people by neighborhood come from the American Community Survey.

January 6, 2021