A brief history of redlining

Inside the 90-year-old financial policy that harms our health

In public health, we often cite structural racism to help explain health patterns in our society. But what, specifically, does this mean? A close look at the history of redlining shows this connection.

When we analyze data on the health of New Yorkers, we often find the same geographic patterns, with higher rates of preventable health conditions in high-poverty neighborhoods. For example, we’ve written about how asthma and poverty are closely connected.

These high-poverty neighborhoods are also home to a higher proportion of people of color than other communities.

The chart below shows the relationship between each neighborhood’s poverty rate and percent population of color, with the rate of childhood asthma ED visits represented by the size of each bubble.

This dynamic extends beyond asthma. To understand why poverty, race, and health are related in New York City, we look back at redlining. This government policy from the 1930s illustrates the nature of poverty and racism in our society - and how racism affects health.

A Brief History of Redlining

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, unemployment rates were high and many people couldn’t make their mortgage payments. A wave of foreclosures swept the country. To help keep people in their homes, the federal government established the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC). Its goal was to refinance mortgages with better terms, like lower interest rates and longer repayment periods, to help people make payments and avoid foreclosure.

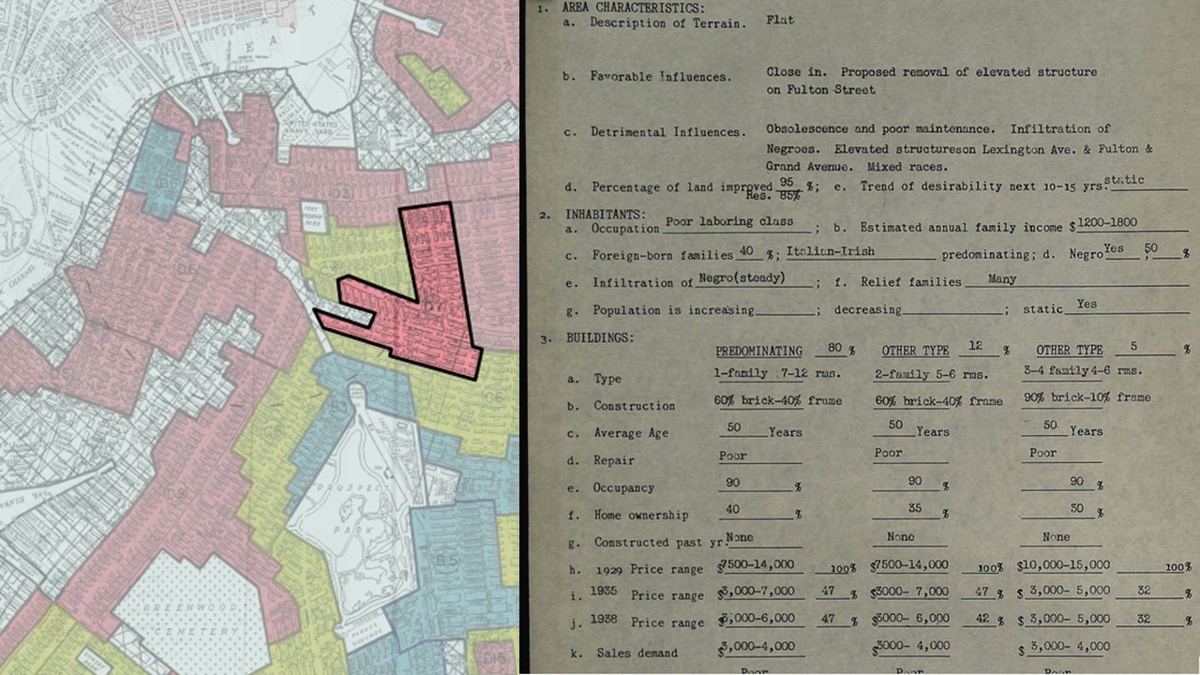

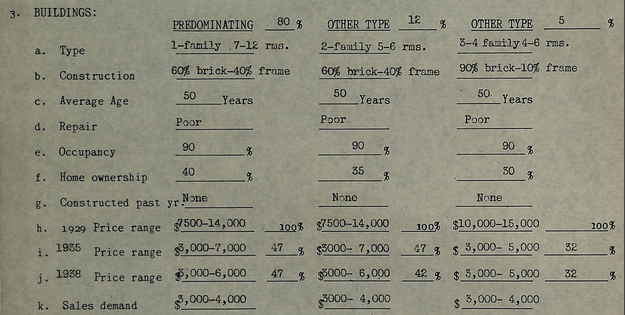

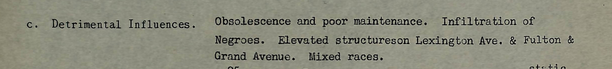

To determine what loans they would guarantee, HOLC sent people to appraise neighborhoods in cities across the US. They documented the types of housing in neighborhoods, along with information about the people who lived there. They also catalogued “detrimental influences,” with racist descriptions like “infiltration of Negroes” and “mixed races" as characteristics that lowered a neighborhood’s value.

With this information, HOLC made “residential security maps” for almost 250 cities, including New York City. On these maps, HOLC gave each neighborhood a classification:

- Best

- Still desirable

- Definitely declining

- Hazardous

The government used these classifications to determine whether to guarantee loans. Banks used them to determine if people were eligible for mortgages, and wouldn’t provide loans to buy homes in the “declining” or “hazardous” neighborhoods.

This was redlining - drawing boundaries around neighborhoods based on residents’ race and depriving them of resources and opportunities - effectively racializing poverty in cities across the U.S.. This is structural racism: where racism is built into the rules of society.

The map below shows the extent of redlining in New York City.

Redlining drove residential segregation

As a result of redlining, people of color were denied access to “desirable” neighborhoods by racist real estate practices - and denied loans to buy homes in neighborhoods labeled “declining” or “hazardous.” Real estate agents also used exploitative tactics like blockbusting, contract selling, and racially restrictive covenants, to deepen and enforce neighborhood segregation.

Blockbusting was a practice used by real estate agents. Since many white people viewed people of color as a social and economic threat to their neighborhoods, agents would tell white homeowners that people of color were about to move into the neighborhood.

This would convince homeowners that their house's value would fall - and they would sell for a lower price. Real estate agents would then turn around and sell property to people of color for inflated prices.

Contract selling was a deceptive and exploitative real estate practice that targeted people of color with private loans to buy homes. These loans often had high interests rates and manipulative terms - in some cases, forcing the buyer to give up their home if they missed even one loan payment.

These contracts often made people responsible for paying back far more money than the house they bought was worth.

A racially-restrictive covenant is a clause in the deed for a property that prevents the owner from selling the property to people of color.

Racially-restrictive covenants were a way to enforce residential segregation, to ensure that people of color were kept out of white neighborhoods.

Owning a home is a powerful way to achieve financial stability. These policies concentrated people of color in neighborhoods deprived of investment and prevented them from accessing loans and buying property - while while white residents were provided more resources and opportunities.

Enormous areas of New York City were redlined. Explore the extent of HOLC’s redlining in NYC’s five boroughs:

Large parts of Manhattan were redlined. However, reinvestment in recent decades has lead to rising property values and the displacement of some former residents. Neighborhoods that were once redlined now have some of the city's most expensive real estate.

As with Manhattan, huge swaths of residential neighborhoods in the Bronx were declared "declining" or "hazardous" in HOLC's redlining map. Unlike Manhattan, though, the Bronx has not seen the same level of reinvestment and redevelopment,and poverty rates remain high.

Brooklyn also saw extensive redlining that lead to deep disinvestment and generations of poverty.

Queens saw significantly less redlining than other boroughs.

Like Queens, Staten Island saw much less redlining than other boroughs.

Redlining’s effects continue today

In New York City, many once-thriving neighborhoods experienced severe disinvestment as a result of redlining, which caused inequality that continued from one generation to the next. Neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s have higher rates of poverty even today – nearly 90 years after the maps were created. According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 3 out of every 4 neighborhoods in the USA that were redlined in the 1930s are still low-to-moderate income today - and 2 out of every 3 are predominantly populated by people of color.

Redlining is a prime example of neighborhood disinvestment: denying or withholding public and private funding, city services, or other resources that neighborhoods - and their residents - need to thrive. When these resources are withheld, it creates “environments that make [people] sick”.

Disinvestment can be:

- Denying people loans to buy homes - like through redlining and other well-documented racist real estate practices

- Housing neglect by landlords, leading to unhealthy housing

- A decline in public funding for housing, schools, and other vital services

- Fewer job opportunities and lower-paying jobs

- Emphasis on policing over pro-social resources

Though redlining was banned in 1968, other forms of housing discrimination persist. But redlining was special: because of how it worsened poverty and segregation in cities across the United States, leaving a legacy of income and racial disparities in health outcomes.

Public health is about far more than changing people’s behaviors at the individual level: it’s about building a society that supports health and well-being, and moving into our future by confronting the past.

More resources about redlining:

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, where you can explore redlining maps and original documents for your neighborhood.

- The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

January 6, 2021